Map number 81 in Vooris [1].

This map includes:

References:

- 1. Voorhis, Ernest [1859–1933]. Historic Forts and Trading Posts of the French Régime and of the English Fur Trading Companies. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1930. University of Britih Columbia Library [accessed 3 January 2026]

Map number 16 in Vooris [

1].

This map includes:

References:

- 1. Voorhis, Ernest [1859–1933]. Historic Forts and Trading Posts of the French Régime and of the English Fur Trading Companies. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1930. University of Britih Columbia Library [accessed 3 January 2026]

Map number 8 in Vooris [

1].

This map includes:

References:

- 1. Voorhis, Ernest [1859–1933]. Historic Forts and Trading Posts of the French Régime and of the English Fur Trading Companies. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1930. University of Britih Columbia Library [accessed 3 January 2026]

Map number 100 in Vooris [

1].

This map includes:

References:

- 1. Voorhis, Ernest [1859–1933]. Historic Forts and Trading Posts of the French Régime and of the English Fur Trading Companies. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1930. University of Britih Columbia Library [accessed 3 January 2026]

Map number 101 in Vooris [

1].

This map includes:

References:

- 1. Voorhis, Ernest [1859–1933]. Historic Forts and Trading Posts of the French Régime and of the English Fur Trading Companies. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1930. University of Britih Columbia Library [accessed 3 January 2026]

America exhibiting principal trading stations of North West Co. in Davidson [

1].

No. 5 in Voorhis [2].

This map includes:

References:

- 1. Davidson, Gordon Charles. The North West Company. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1918. Internet Archive [accessed 27 December 2025]

- 2. Voorhis, Ernest [1859–1933]. Historic Forts and Trading Posts of the French Régime and of the English Fur Trading Companies. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1930. University of Britih Columbia Library [accessed 3 January 2026]

An accurate map of North America. Describing and distinguishing the British, Spanish and French dominions on this great continent; according to the definitive treaty concluded at Paris 10th Feby. 1763. Also all the West India Islands belonging to, and possessed by the several European princes and states. The whole laid down according to the latest and most authentick improvements.

London, Printed for Robt. Sayer.

Attributed to Welsh cartographer Emanuel Bowen [1694–1767].

Ernest Voorhis [1859–1933] in Historic Forts and Trading Posts says this map shows Jasper House, which he says was built in 1799 at outlet of Brûlé Lake and called Rocky Mountain House [1].

This map includes:

References:

- 1. Voorhis, Ernest [1859–1933]. Historic Forts and Trading Posts of the French Régime and of the English Fur Trading Companies. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1930, Map No. 98. University of British Columbia Library [accessed 3 January 2026]

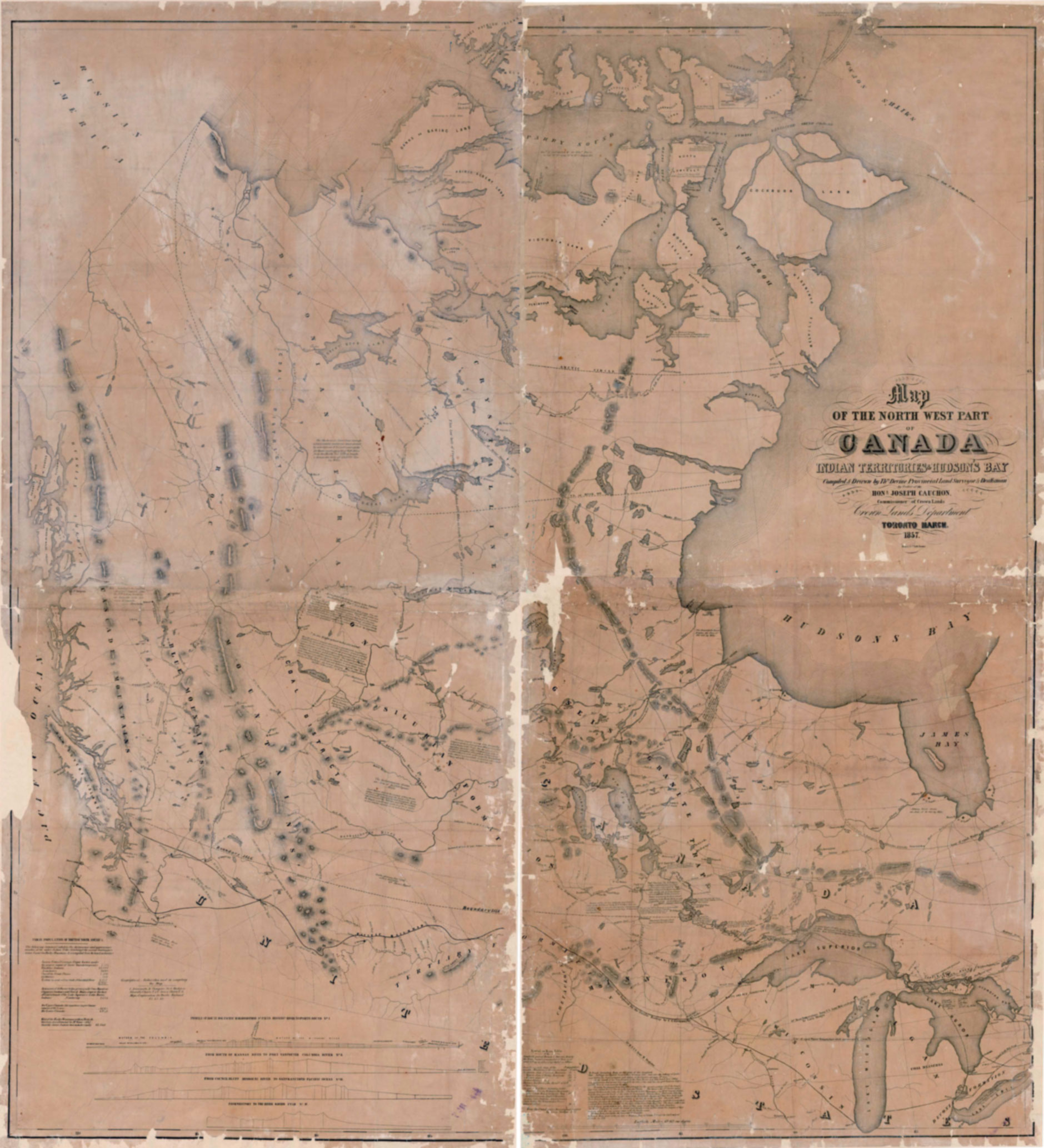

Map

of the North West Part of Canada.

Indian Territories & Hudson’s Bay

Compiled & Drawn by Thos. Devine

Provincial Land Surveyor & Draftsman

by Order of the Hon. Joseph Cauchon, Commissioner of Crown Lands Crown Lands Department

Toronto March, 1857.

Map No. 12 in Voorhis [1].

This map includes:

References:

- 1. Voorhis, Ernest [1859–1933]. Historic Forts and Trading Posts of the French Régime and of the English Fur Trading Companies. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1930. University of Britih Columbia Library [accessed 3 January 2026]

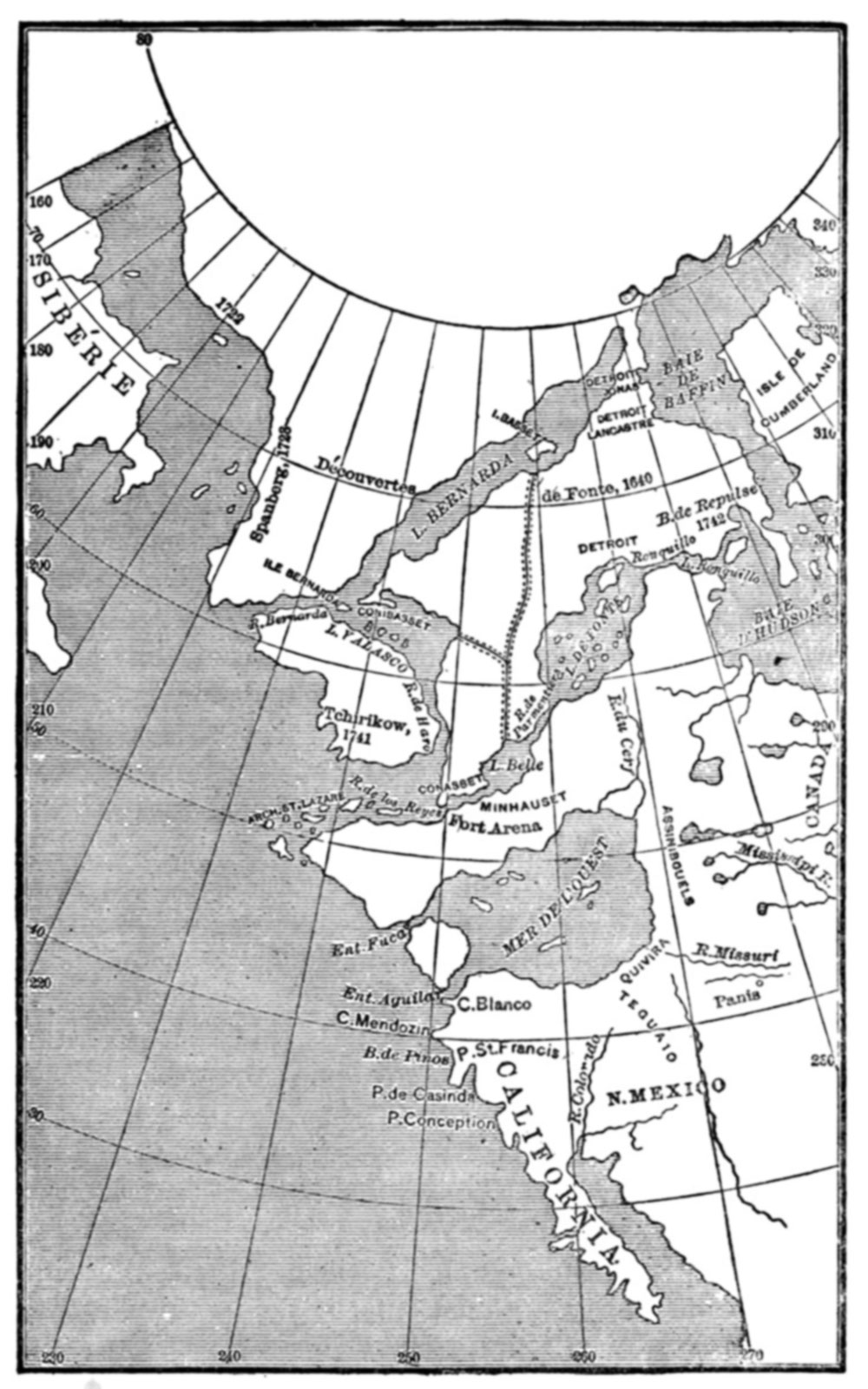

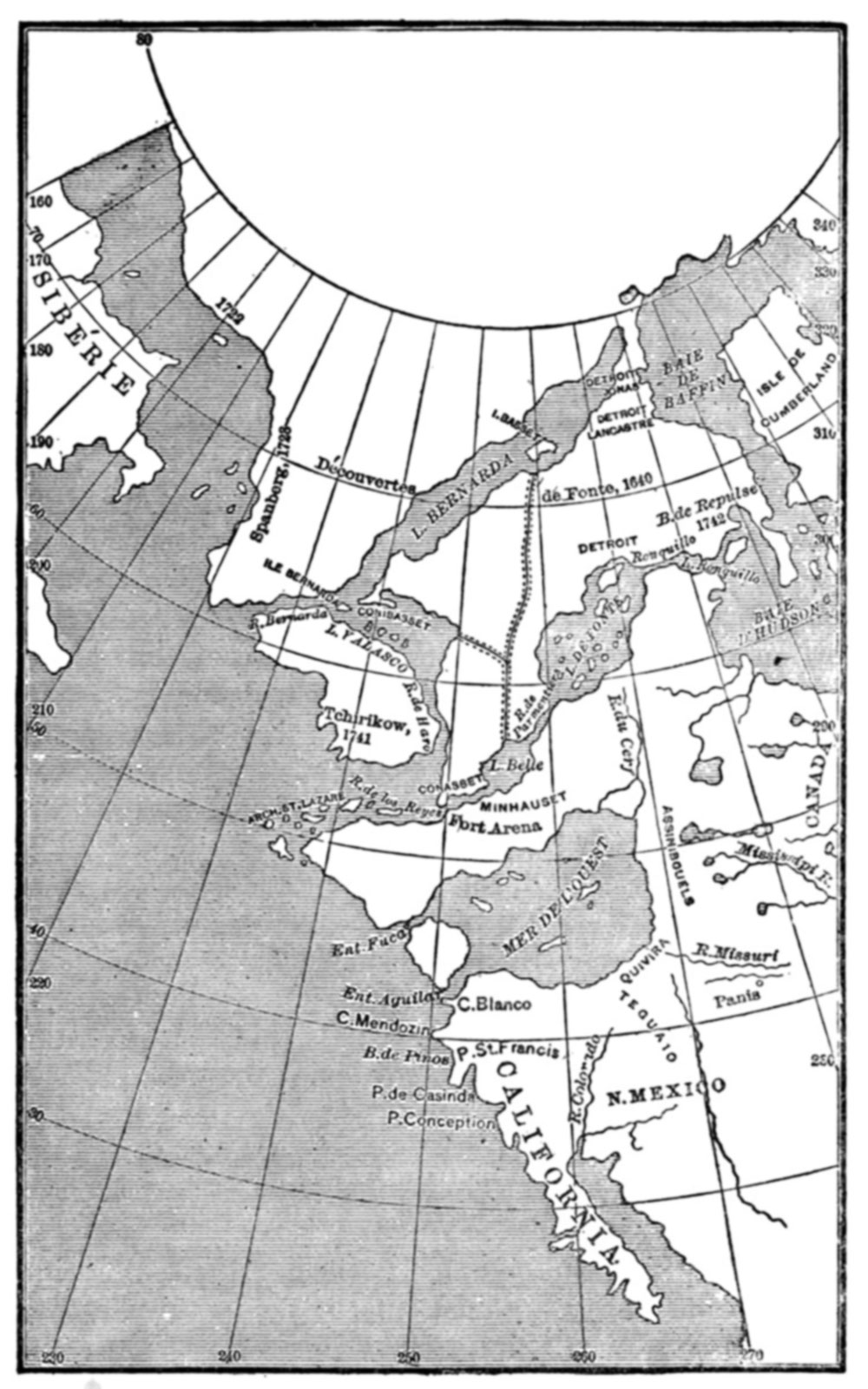

De L’Isle’s map 1752

Gutenberg [accessed 17 January 2026]

This map includes:

References:

- 1. Willson, Henry Beckles [1869–1942]. The Great Company. Being a History of the Honourable Company of Merchants-Adventurers Trading Into Hudson’s Bay. 1900. Gutenberg [accessed 17 January 2026]

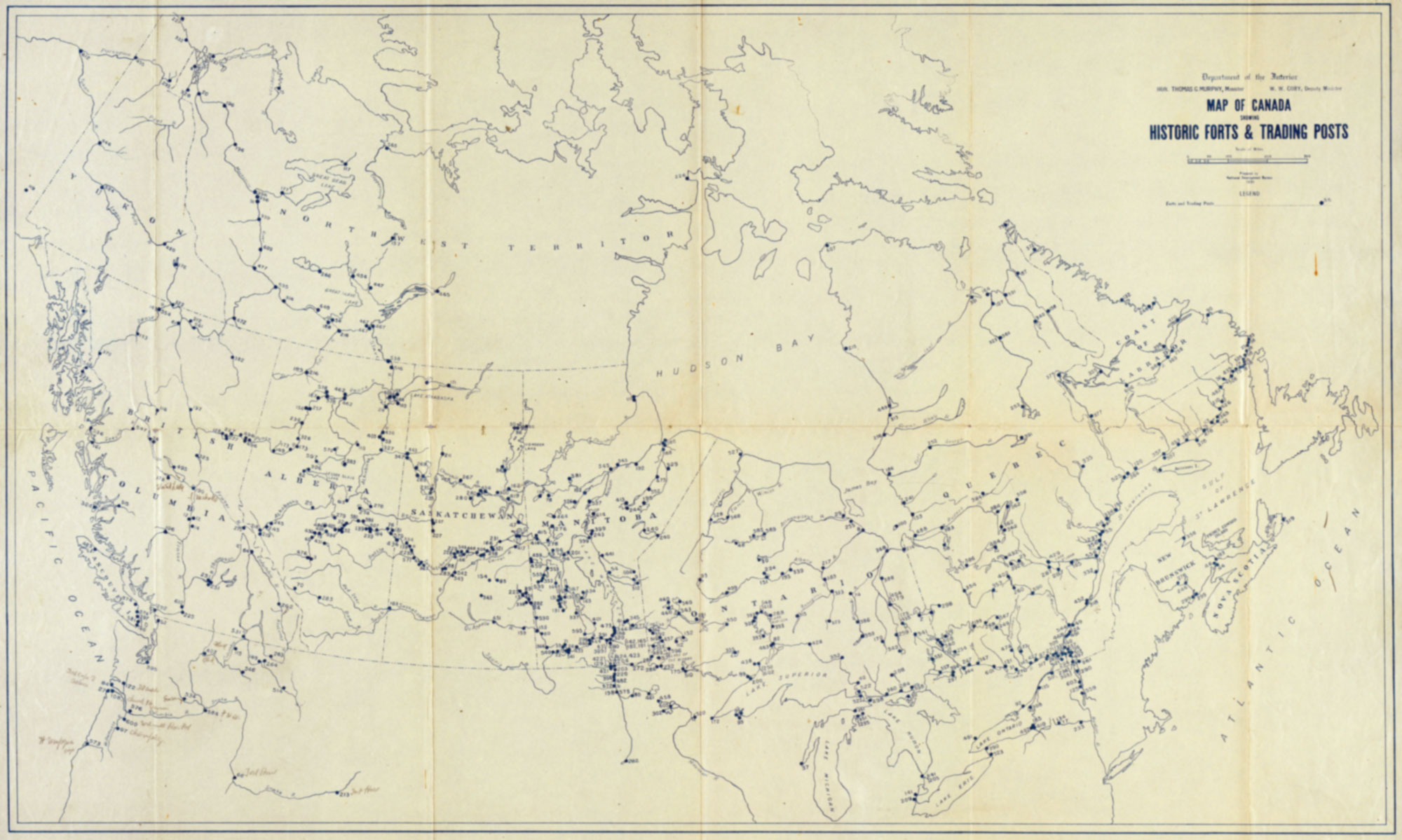

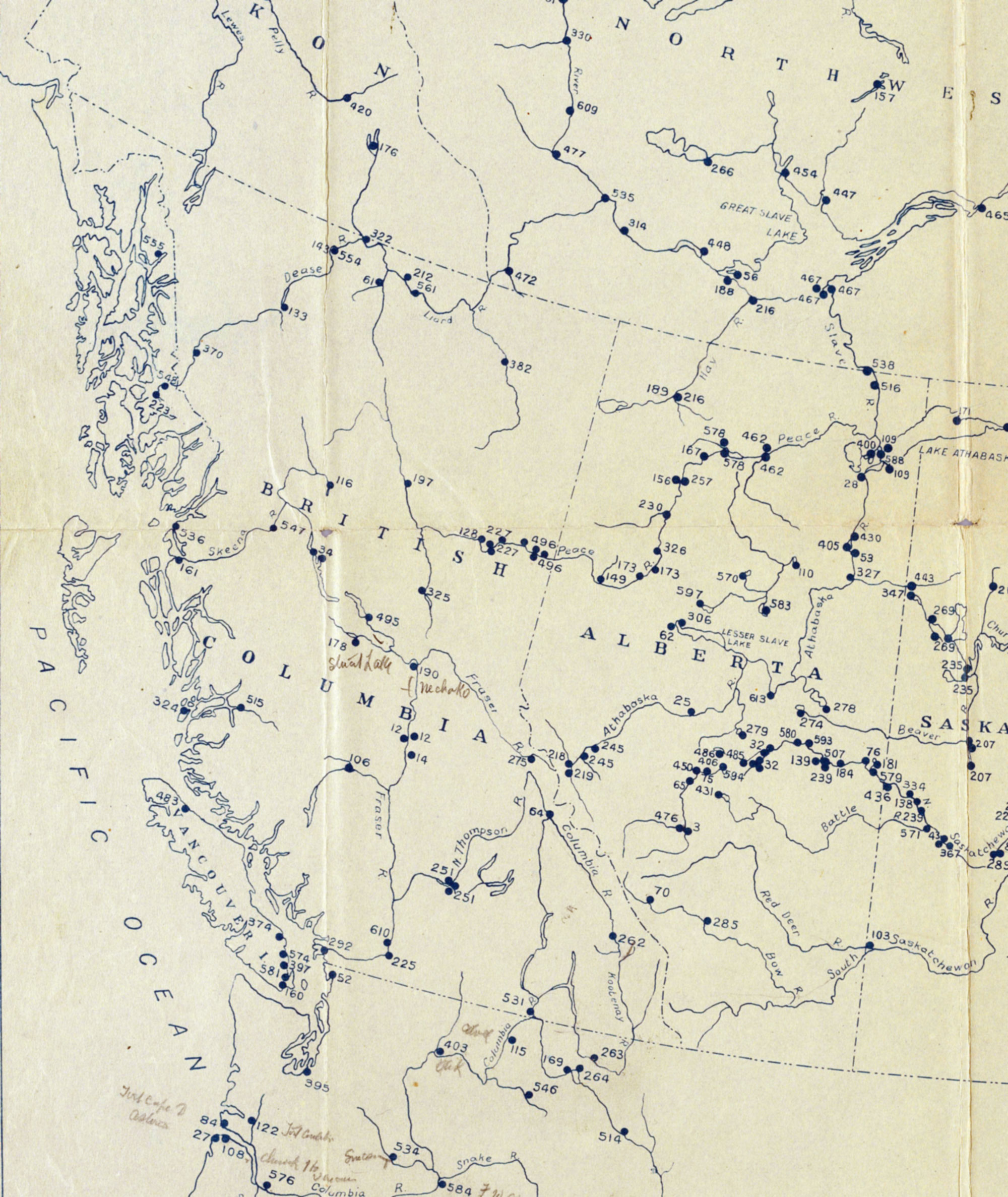

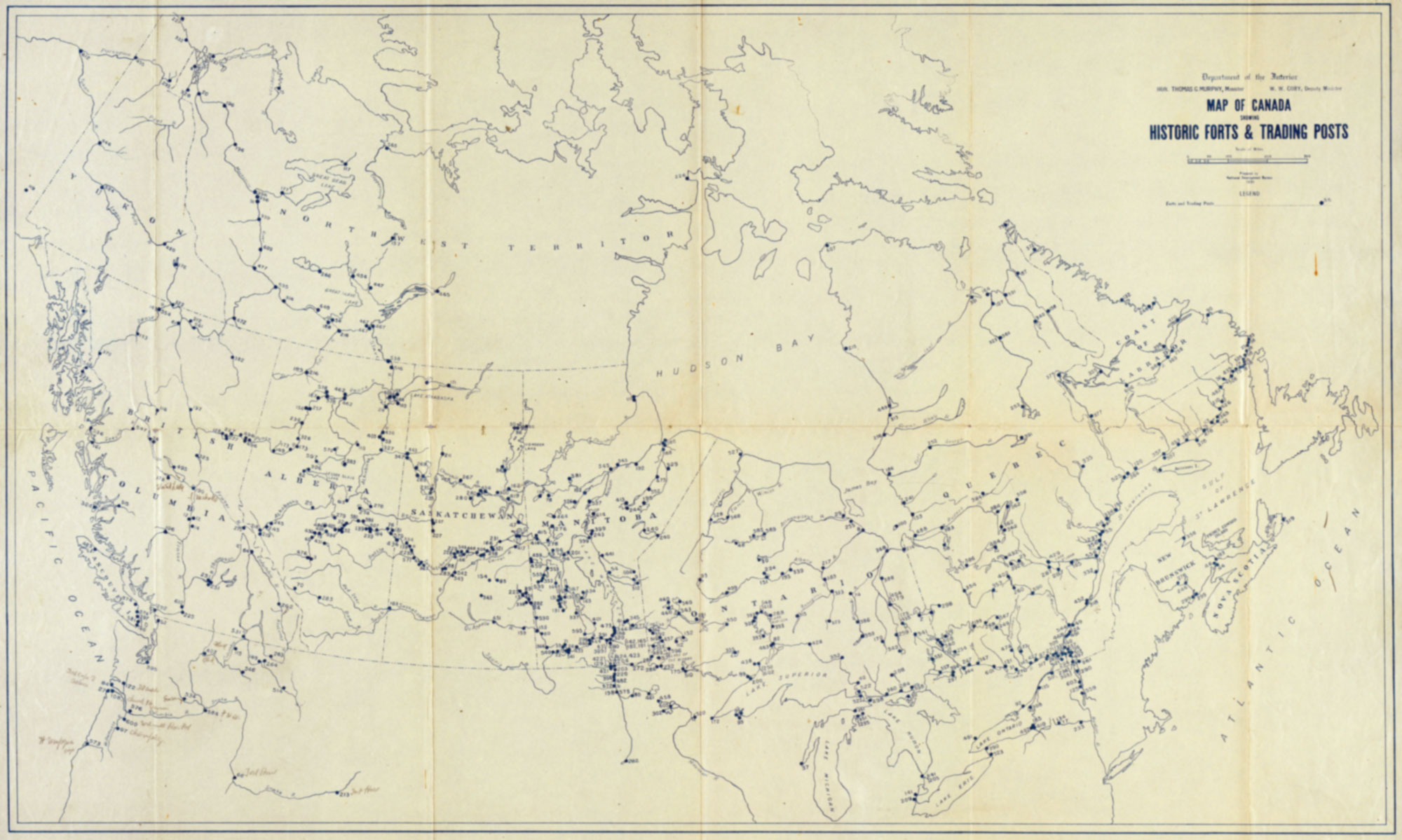

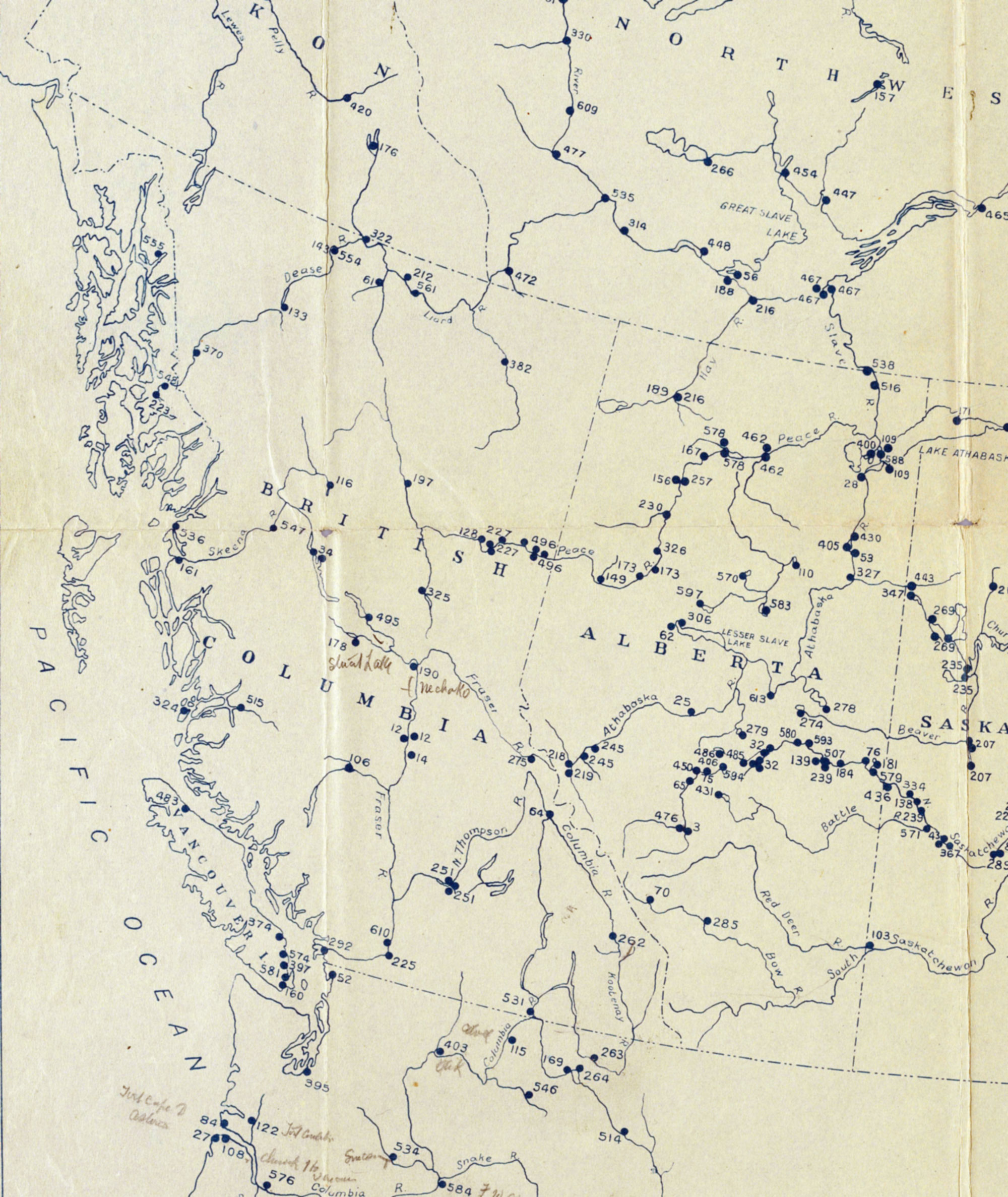

Map of Canada showing Historic Forts & Trading Posts.

Department of the Interior, 1920

Detail

Map of Canada Showing Historic Forts and Trading Posts

Department of the Interior, 1930

Prepared by National Development Bureau

This map includes:

References:

- Voorhis, Ernest [1859–1933]. Historic Forts and Trading Posts of the French Régime and of the English Fur Trading Companies. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1930. University of Britih Columbia Library [accessed 3 January 2026]