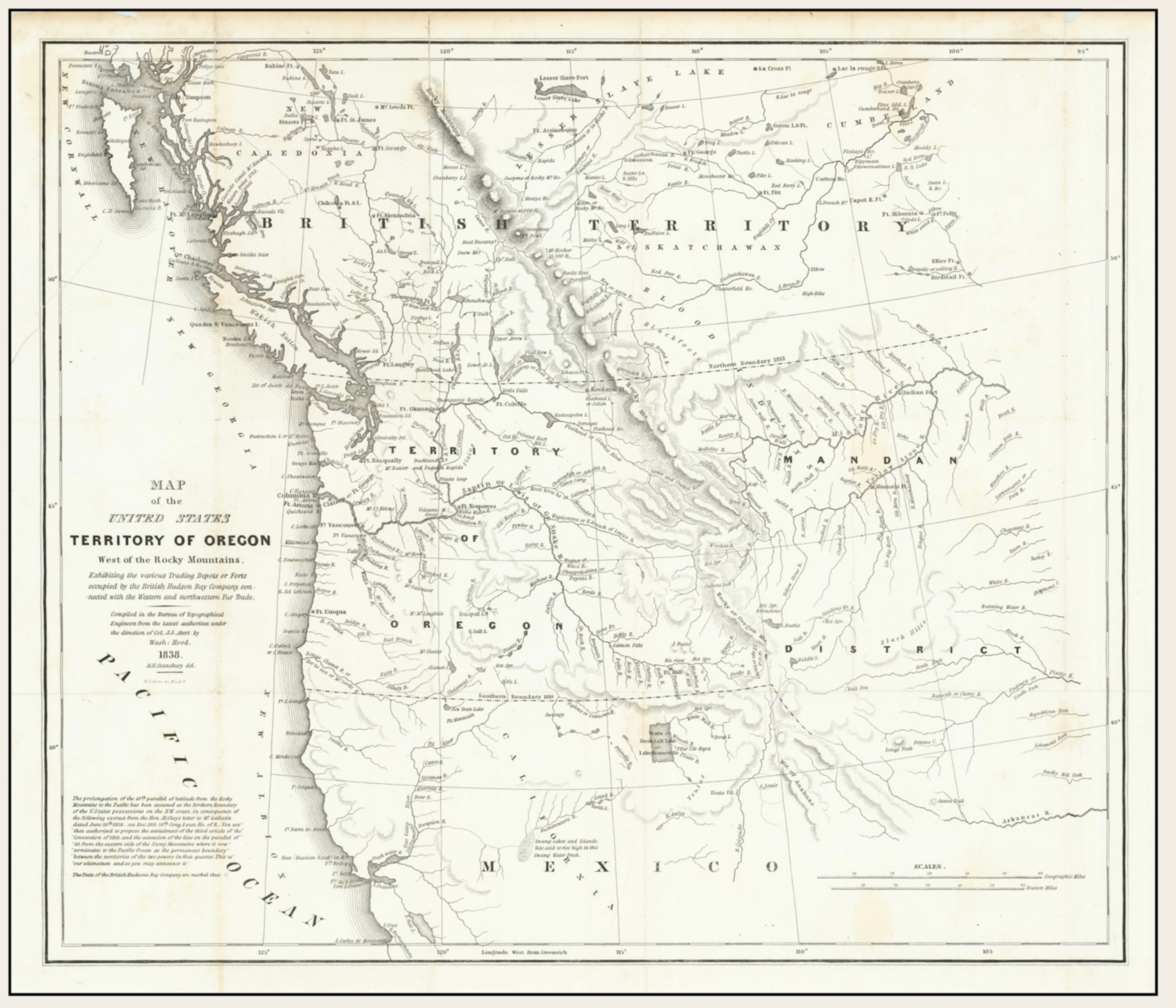

Map of the United States Territory of Oregon West of the Rocky Mountains.

Hood 1838

RareMaps

![Map of the United States Territory of Oregon West of the Rocky Mountains [detail] Hood 1838](/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/map-hood-oregon-1838-detail-scaled.jpg)

Map of the United States Territory of Oregon West of the Rocky Mountains [detail]

Hood 1838

RareMaps

Map of the United States

Territory of Oregon

West of the Rocky MountainsExhibiting the various Trading Depots or Forts occupied by the British Hudson Bay Company connected with the Western and northwestern Fur Trade.

Compiled in the Bureau of Topographical Engineers from the latest authorities, under the direction of Col. J. J. Abert, by Wash: Hood.

1838

Showing Oregon Territory used during Congressional Debates about the Status of Oregon Country. The Hood map follows Aaron Arrowsmith’s map of 1834.

Hood’s landmark map of the Oregon Country was integral to political debates about the area, its place in the growing United States, and its boundary with Britain. It was made by Washington Hood, a Captain in the US Army and one of the first members of the fledgling Corps of Topographical Engineers, in 1838.

The map depicts North America west of the Mississippi River, which is not shown. In geography, the map closely follows Aaron Arrowsmith’s 1834 map of North America and adopts a similar, clean style. In the “Territory of Oregon,” a designation the area did not yet officially have, the Columbia River is the dominating feature, with forts and outposts of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) marked. To the north, the “British Territory” is demarcated by a dotted and dashed line at the 49th parallel. The choice of this boundary was not clear cut and reveals the intense debates that occurred around the time this map was made regarding Oregon’s status within the United States.

Acton House [as “Acton or Rocky Mt. Ho.”]

Athabasca River [as “Athabasca or la Birche R.”]

Boat Encampment

Mount Brown [as “M. Browne 16,000 ft.”]

Canoe River

Committee Punch Bowl [as “Committees Ph. Bowl”]

Columbia River

Cranberry Lake

Fort St. James

Fort Fraser

Fort George

Henry’s House (1)

Mount Hooker [as “Mt. Hooker 15,700 ft.”]

Jasper House [as “Jaspens or Rocky Mn. Ho.”]

McLoud’s Fort

Moose Lake

Rocky Mountains

Rocky Mountain House [as “Acton or Rocky Mt. Ho.”]

Smoky River

South Fork Fraser River [as “Gt. Fork”]