McGregor River

54.1794 N 122.0336 W Google — GeoHack

Not currently an official name.

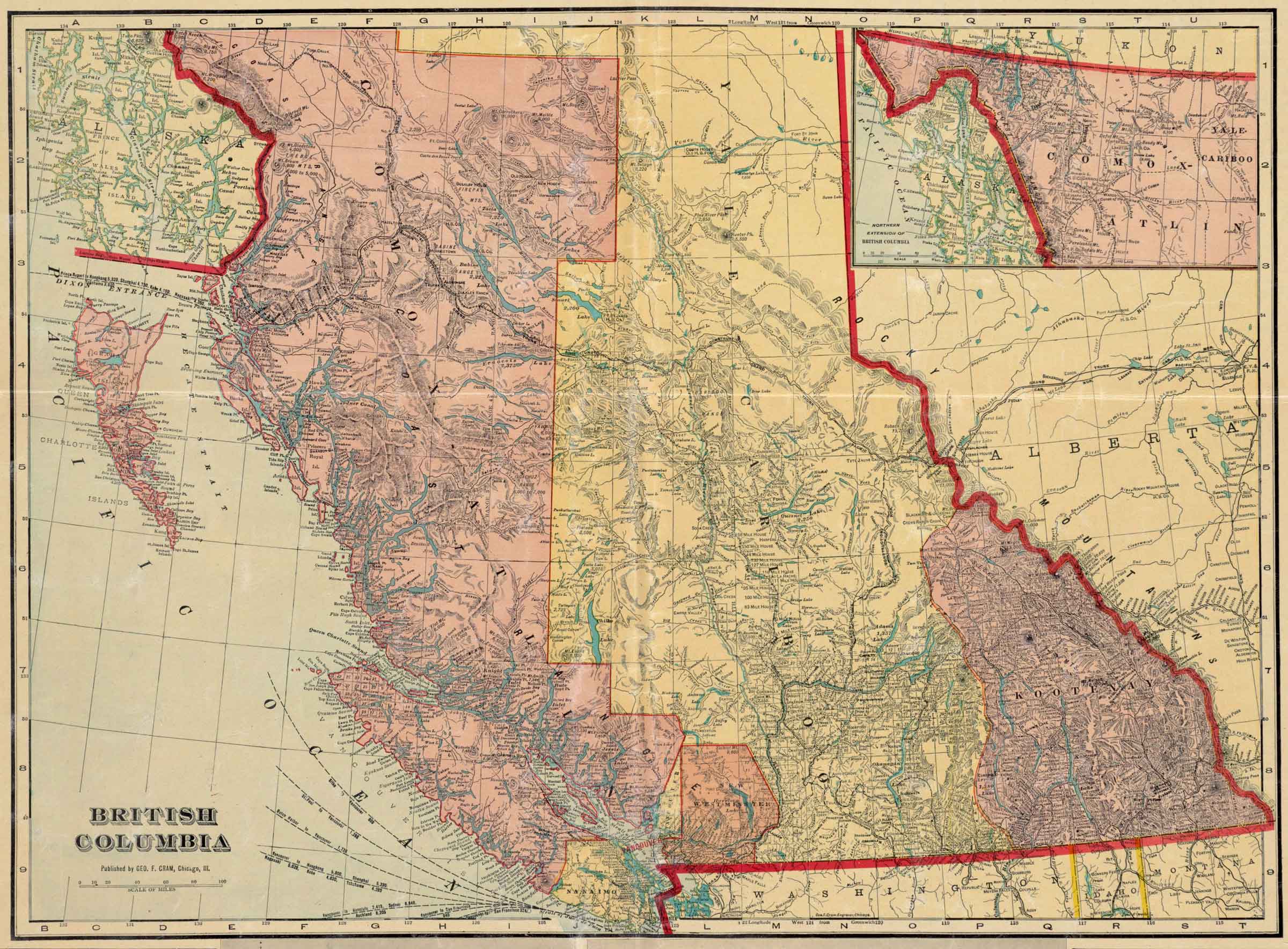

British Columbia.

Published by Geo. F. Cram, Chicago,Ill.

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center

![British Columbia [detail].

Published by Geo. F. Cram, Chicago,Ill.](/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/map-cram-british_columbia-1913-detail.jpg)

British Columbia [detail].

Published by Geo. F. Cram, Chicago,Ill.

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center

George Franklin Cram [1842-1928] was an American map publisher. He served in the U.S. Army during the American Civil War. Upon mustering out he joined his uncle Rufus Blanchard’s Evanston, Illinois, map business in 1867. Two years later, he became sole proprietor of the firm and renamed it the George F. Cram Co. which became a leading map firm in the United States.

The map indicates the constructon of both the Grand Trunk Pacific Railwayand the Canadian Northern Railway, both traversing the Yellowhead Pass and branching at Tête Jaune Cache.

On the Grand Trunk route following the Fraser River between Tête Jaune Cache and Fort George there are no settlements indicated. South of Tête Jaune Cache the first settlements along the CNoR are near Kamloops on the North Thompson River.

Indigenous people

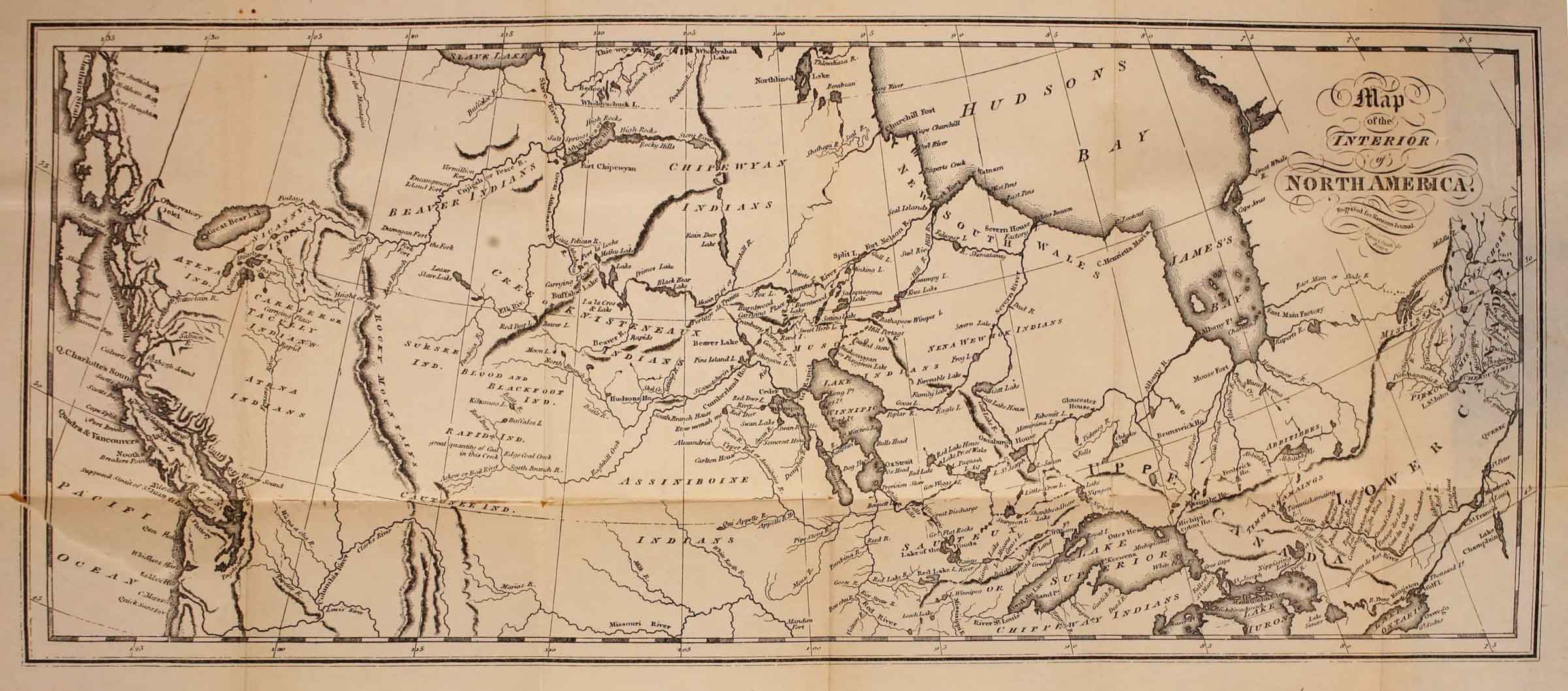

Harmon’s map interior of North America 1820 shows the following Indian distribution:

East of the Rocky Mountains:

Beaver Indians — around the Peace River from headwaters to Fort Chipewyan

Cree or Knisteneaux Indians — around the Saskatchewan River drainage

Sursee Indians — around headwaters of the Athabasca River

West of the Rockies:

Sicanny Indians — north of Fraser River

Carrier (Dakelh) or Tacully Indians — around upper Fraser River

Peter Pond’s maps of 1785 and 1787 refer to the River of Peace.

Other names have included Un-ja-ga/Unjigah, as recorded on a map to accompany Mackenzie’s “Voyage to the Pacific… 1793”

Map of the interior of North America, engraved for Harmon’s Journal Internet Archive

Harmon arrived in New Caledonia in 1809. There he served for ten years at Fort Saint James and Fort Fraser.

The map seems largely based on Mackenzie’s map North America 1803.

Rupert’s Land (French: Terre de Rupert), or Prince Rupert’s Land (French: Terre du Prince Rupert), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin. The right to “sole trade and commerce” over Rupert’s Land was granted to Hudson’s Bay Company, based at York Factory, effectively giving that company a commercial monopoly over the area. The territory operated for 200 years from 1670 to 1870. Its namesake was Prince Rupert of the Rhine, who was a nephew of King Charles I and the first governor of HBC.

In December 1821, the HBC monopoly was extended from Rupert’s Land to the Pacific coast.

Rupert’s Land included the drainage of the Saskatchewan River.

The Rupert’s Land Act 1868, which was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom, authorized the sale of Rupert’s Land to Canada with the understanding that it included the whole of the lands and territories held or claimed to be held by the Hudson’s Bay Company

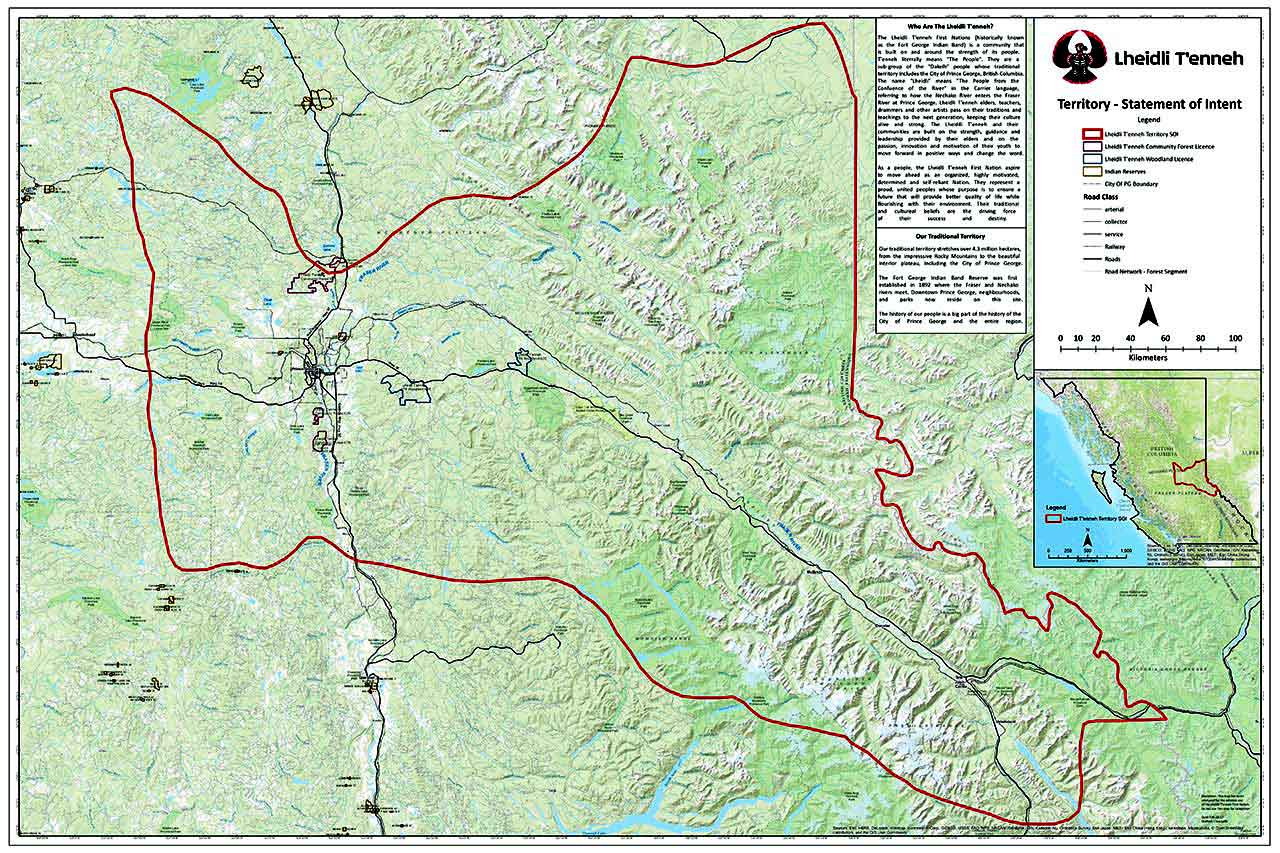

Lheidli T’enneh Territory Lheidli T’enneh First Nation

A Shaman or “Medicine Man.” Morice 1904, p. 10 Internet Archive

A Carrier Fisherman. Morice 1904, p. 40 Internet Archive

Doubly “Carriers.” Morice 1904, p. 163 Internet Archive

Carrier and Carried. Morice 1904, p. 218 Internet Archive4

The Carrier or Dakelh are the indigenous people of a large portion of the Central Interior of British Columbia, belonging to the Northern Athabascan or Dene group of First Nations.

Among the Carriers, the widow of a deceased warrior used to pick up from among the ashes of the funeral pyre the few charred bones which would escape the ravages of fire and carry them on her back in a leathern satchel—hence the name of the tribe—until the co-clansmen of the deceased had amassed a sufficient quantity of eatables and dressed skins to be publicly distributed among people of different clans, in the course of an ostentatious ceremony called “potlatch,” a ceremony which prevailed among all but the Sekanais and the Eastern Nahanais tribes.

— Morice 1904, p. 6 [1]

The Carrier lived directly north of the Chilcotin, in the valleys of the upper Fraser, Blackwater, Nechako, and Bulkley rivers, and around Stuart and Babine lakes up to the borders of Bear lake. Their name (English, Carrier; French, Porteur, said to be a translation of the term applied to them by their eastern neighbours, the Sekani) refers to their peculiar custom of compelling widows to carry on their backs the charred bones of their dead husbands. They had no common name for themselves, only names for the independent sub-tribes into which they were divided. In the nineteenth century, however, they adopted for themselves the obscure title Takulli, bestowed on them apparently by Europeans.

— Jenness 1932 [2]

Dakelh territories include along Fraser River from south of Quesnel upstream to the Yellowhead Pass, as well as the upper North Thompson and Canoe River valleys.

The traditional Dakelh way of life is based on a seasonal round, with the greatest activity in the summer when berries are gathered and fish caught and preserved. The mainstay of the economy is centered on harvesting activities within each family keyoh (territory, village, trapline) under the leadership of a hereditary chief, known as a Keyoh holder or keyoh-whudachun. Fish, especially the several varieties of salmon, are smoked and stored for the winter in large numbers. Hunting and trapping of deer, caribou, moose, elk, black bear, beaver, and rabbit provided meat, fur for clothing, and bone for tools. Other fur-bearing animals are trapped to some extent, but until the advent of the fur trade, such trapping is a minor activity.

The Dakelh engaged in extensive trade with the coast along trails known as “grease trails”. The items exported consisted primarily of hides, dried meat, and mats of dried berries. Imports consisted of various marine products, the most important of which was “grease”, the oil extracted from eulachons (also known as “candlefish”) by allowing them to rot, adding boiling water, and skimming off the oil. This oil is extremely nutritious and, unlike many other fats, contains desirable fatty acids. [3]

The band located near Prince George is the Lheidli T’enneh Band, [4] historically known as the Fort George Indian Band. The Lheidli T’enneh did not have permanent settlements in what is modern day Prince George until the arrival of the Hudson’s Bay Company post Fort George. Temporary and seasonal settlements were used across the traditional territory and archeological evidence of fishing camps along the Nechako and Fraser rivers.

Secwepemcúĺecw, the traditional territory or country of the Shuswap people, ranges from the eastern Chilcotin Plateau, bordering Tŝilhqot’in Country, and the Cariboo Plateau southeast through Thompson Country to Kamloops. It spans the Selkirk Mountains and Big Bend of the Columbia River to include the northern part of the Columbia Valley region. Their traditional territory covers approximately 145,000 square kilometres Traditionally, they depended on hunting, trading and fishing to support their communities. [1]

Milton and Cheadle were at Jasper House in 1863, preparing to cross the Yellow Head Pass.

During the day several more half-breeds arrived with their wives and families, and in the evening two Shuhswap Indians made their appearance, and set to work to spear white-fish by torchlight. These were the first specimens of their tribe which we had seen. They were lean and wiry men, of middle stature, and altogether of smaller make than the Indians we had met before; their features were also smaller, and more finely cut, while the expression of their faces was softer and equally intelligent. They were clothed merely in a shirt and marmot robe, their legs and feet being naked, and their long black hair the only covering to their heads. These Shushwaps of the Rocky Mountains inhabit the country in the neighborhood of Jasper House, and as far as Tête Jaune Cache on the western slope. They are a branch of the Shushwap nation, who dwell near the Shushwap Lake and grand fork of the Thompson River in British Columbia. Separated from the main body of their tribe by 300 or 400 miles of almost impenetrable forest, they hold but little communication with them. Occasionally a Rocky Mountain Shushwap makes the long and difficult journey to Kamloops on the Thompson, to seek a wife. Of those we met, only one had ever seen this place. This was an old woman of Tête Jaune Cache, a native of Kamloops, who had married a Shushwap of the mountains.

When first discovered by the pioneers of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the only clothing used by this singular people was a small robe of the skin of the mountain marmot. They wandered barefoot amongst the sharp rocks, and amidst the snow and bitter cold of the fierce northern winter. When camping for the night they are in the habit of choosing the most open spot, instead of seeking the protection of the woods. In the middle of this they make only a small fire, and lie in the snow, with their feet towards it, like the spokes of a wheel, each individual alone, wrapped in a marmot robe, the wife apart from the husband, the child from its mother. They live by hunting the bighorns, mountain goats, and marmots; and numbers who go out every year never return. Like the chamois hunters of the Alps, some are found dashed to pieces at the foot of the almost inaccessible heights to which they follow their game; of others no trace is found. The Shushwaps of Jasper House formerly numbered about thirty families, but are now reduced to as many individuals. Removed by immense distances from all other Indians, they are peaceable and honest, ignorant of wickedness or war. Whether they have any religion or not, we could not ascertain; but they enclose the graves of their dead with scrupulous care, by light palings of wood, cut, with considerable neatness, with their only tools — a small axe and knife. They possess neither horses nor dogs, carrying all their property on their backs when moving from place to place; and when remaining in one spot for any length of time, they erect rude slants of bark or matting for shelter, for they have neither tents nor houses. As game decreases the race will, doubtless, gradually die out still more rapidly, and they are already fast disappearing from this cause, and the accidents of the chase.

— Milton and Cheadle, 1863 [2]