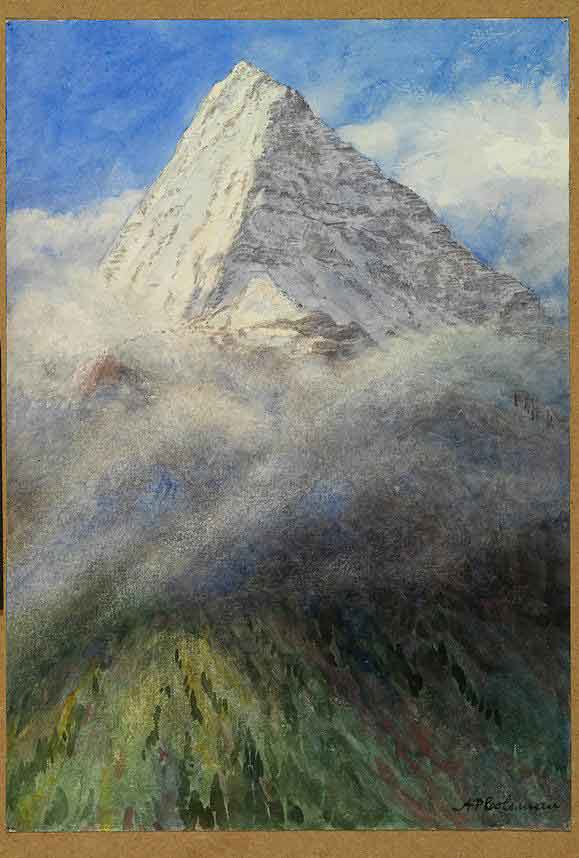

NW ridge of Mount Robson

53.1148 N 119.1727 W Google — GeoHack

Not currently an official name.

Mount Robson from North West, 1908

Arthur Philemon Coleman

Watercolour over pencil on paper Royal Ontario Museum [accessed 15 February 2025]

Arthur Philemon Coleman [1852–1939] explored the Mount Robson area in 1907 and 1908, with a party that included George R. B. Kinney [1872–1961]. Kinney made an attempt to climb Mount Robson with Donald “Curly” Phillips [1884–1938] in 1909, nearby this ridge. The ridge was not sucessfully climbed until 1961, when Ronald Perla and Tom Spencer reached the summit.

- Coleman, Arthur Philemon [1852–1939]. The Canadian Rockies: New and Old Trails. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1911. Internet Archive [accessed 3 March 2025]

- Kruszyna, Robert, and Putnam, William Lowell [1924–2014]. The Rocky Mountains of Canada north. 7th Edition.. New York and Banff: The American Alpine Club and the Alpine Club of Canada, 1985