Palliser expedition member

James Hector [1834–1907], who was in the

Jasper House area in 1857, relates:

There was once a little tribe of Indians known as the Snakes, that lived in the country to the north of Jasper House, but which, during the time of the North West Fur Company, was treacherously exterminated by the Assineboines. They were invited to a peace feast by the latter Indians, when they were to settle all their disputes, and neither party was to bring any weapons. It was held about three miles below the present site of Jasper House, but the Assineboines being all secretly armed, fell on the poor Snakes in the midst of the revelry, and killed them all. Such was the story I heard from the hunters here.

In 1861 Henry John Moberly [1835–1932] met “the last of the Snake Indians” living with Shuswap (Secwépemc) people at Tête Jaune Cache:

At Jasper I induced a young halfbreed to join me and try his luck in British Columbia. We started in company across the pass to Tête Jaune Cache, the snow a foot deep on the ground and the streams frozen over but not solid enough to bear us. We were obliged, therefore, to cut our way through brush and fallen timber at points where we should otherwise have followed a creek-bed. Six days of this brought us to Tete Jaune, where we planned to embark.

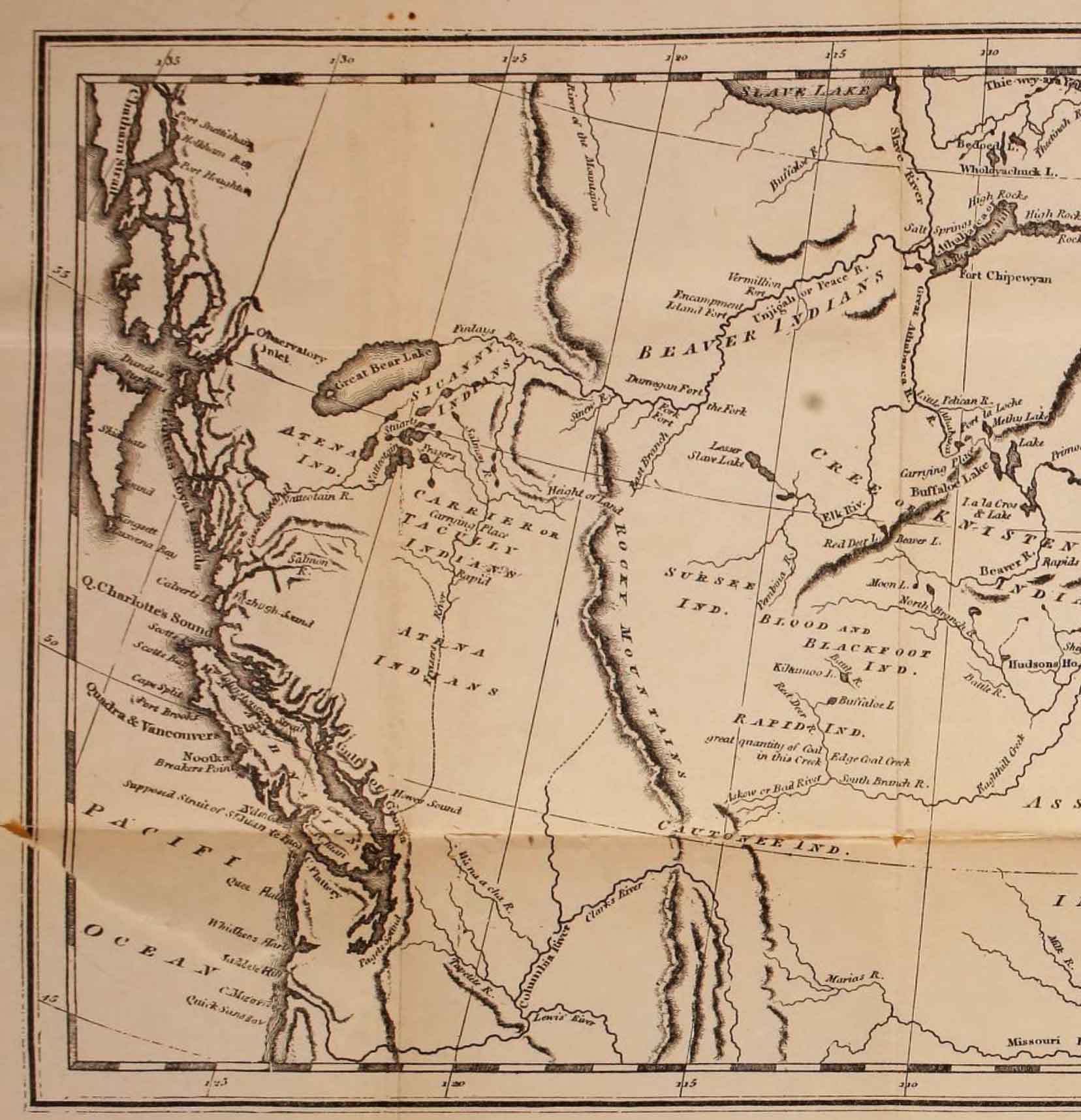

At the Cache we found encamped a small band of Shushwaps, among them a woman, the last member of a petty tribe called the Snake Indians. From the Shushwaps I procured a dugout and some fresh provisions. They gave me also a description of the river as far as the Hudson’s Bay post named Fort George, close to the forks of the Stuart [Nechako] and Fraser rivers.

The Snake woman just mentioned had lived through one of the most remarkable experiences of which I have ever heard. Eighteen or nineteen years before [ca 1842] her tribe had consisted of some twenty families, living entirely in the mountains and for decades at war with the wood Assiniboines. The Snakes at the time of which I write were camped on the side of a mountain west of the post [Jasper House], and a band of Assiniboines at Lac Brule, just below the entrance to the pass. The Assiniboines proposed a meeting at the head of the lake for the purpose of ratifying a peace, each band to come unarmed.

The Snakes agreed, and the men of the band, leaving their guns, arrived and were placed in the inner circle around the council fire. The Assiniboines, however, concealed their guns under their blankets and at a prearranged signal drew them and shot down in cold blood every man of their ancient enemies. They then rushed to the Snake camp and wiped out the rest of the band, with the exception of three young women whom they brought as prisoners to Fort Assiniboine. Here they were stripped, bound and placed in a tent, to be tortured and finally dispatched at a great scalp dance to be held next day.

During the night a French halfbreed, Bellerose by name, crept into the lodge where the prisoners lay and cut their bonds. All he could provide them was his scalping knife and a fire bag containing flint, steel and punk. The women made their escape….

In Indigenous cultures, the term snake is a generic pejorative used to describe other tribes, regardless of their actual ancestry, hence the many locations in Alberta where a number of different tribes lived, all of whom, although unrelated, were called “Snakes.” From 1688-1720s, when the British Empire first came into prolonged trade contact with the Western Cree and Blackfoot, both of these groups were united in a war against “the Snake Indians” of Canada. It is not clear if this term (used in this period of Canadian history) is meant to refer to the Northern Paiute people, inaccurate, or perhaps entirely unrelated. In modern Plains Cree language, the term “kinêpikoyiniwak / ᑭᓀᐱᑯᔨᓂᐘᐠ,” literally translating to “Snake Indian” refers to Shoshone people.[3]