Kinbasket Lake is named for a chieftain of the

Shuswap (Secwépemc) people who inhabited the valleys of the upper Columbia River and upper

North Thompson River.

Walter Moberly [1832–1915] met Kinbasket, whom he referred to as “Kinbaskit,” in 1866.

We crossed the Columbia river, and at a short distance came to a little camp of Shuswap Indians, where I met their headman, Kinbaskit. I now negotiated with him for two little canoes made of the bark of the spruce, and for his assistance to take me down the river. Kinbaskit was a very good Indian, and I found him always reliable. We ran many rapids and portaged others, then came to a Lake which I named Kinbaskit Lake, much to the old chief’s delight. (1)

In 1872, they met again when Kinbasket guided a survey party for the Canadian Pacific Railway near Howse Pass. Robert M. Rylatt [fl. mid-1800s], a member of the party, referred to him as “Kimbasket.” Rylatt wrote in his memoirs:

On Saturday I had another Indian visitor, Old Kimbasket, the head chief of the Kootenay Indians, a daring, little shriveled up old fellow, but whom I was glad to see, and with whom I suddenly became acquainted with the Chinook jargon again.… This old chief Kimbasket is in the employ at present, and his principal occupation is blazing; that is to say, his duty is to be in advance of the party, and blaze the best route to be followed in making the trail, by blazing trees within sight of each other; or, should this not be clearly understood, blazing signifies chipping the bark off the trees for about a foot, so as to be clearly desernable to the party following.…

Seven miles beyond here the [Columbia] river opens up into a lake, which has been named after the old chief “Kimbasket Lake.” This lake is some 20 miles in length, and using the boats over this surface would be a great saving of time and labor, and would rest the animals considerably. [p. 76]

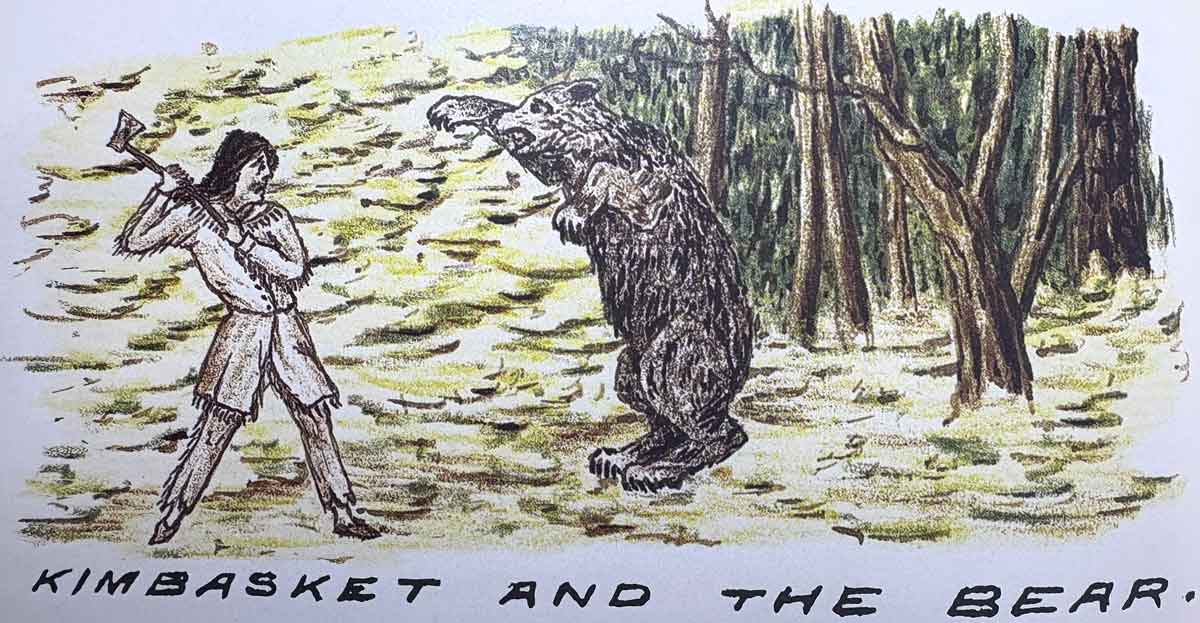

Tuesday, Augt 20th [1872] Poor old Chief Kimbasket has come to grief. He was in his place a day or two ago, or in other words was somewhat in advance of the party blazing the route, when of a sudden he was set upon by a bear, and having no arms save his light axe, his bearship took him at advantage; the rush to the attack was so sudden, and the animal apparantly so furious, the old chief had barely time to raise the axe and aim a blow as the brute raired, ’ere his weapon was dashed aside like a flash, and he was in the embrace of the monster, the huge forepaws around him, the immense claws dug into his back, the bear held him up; then fastening the poor chiefs shoulder in his iron Jaws, he raised one of his hind feet, and tore a fearful gash; commencing at the abdomen, and cutting through to the bowels, he fairly stripped the flesh and muscles from one of his thighs, a bloody hanging mass of flesh and rent cloth-ing. Thus he was found the following morning, being too weak and torn to attempt to reach camp. What a night of suffering he must have had. Green, who by the way has studied medicine, and is considerable of a doctor, says he hopes to bring him round all right, but that he has had a narrow squeek for it. As soon as he can travel, he will be sent off with the Indians who will shortly be leaving us. [p. 85]

It was on the shores of this lake Kimbasket was so fearfully mangled, it remains a mystery to me why the brute did not quite finish the poor chief ‘ere leaving him. [p. 91] (2)

Moberly also describes the bear attrack:

Kinbaskit and the two Indians soon returned with the bear, but poor Kinbaskit was rather badly wounded, which occurred, as the Indians toldme, in the following way. They traced the wounded animal by the blood,and found him lying alongside a log. Kinbaskit thought he was so badlywounded he could do no harm, and advanced with only a heavy stick in hishand to despatch him; but when, quite close the bear suddenly stood upon his hind legs and struck Kinbaskit with one of his paws, giving himsevere wounds on the scalp and tearing the flesh of his arm and hand very badly, when the Indian, Tim, shot the bear dead. It was quite a surgical work, sewing and plastering up the old chiefs wounds, who appeared quite unconcerned.

The lake was noted by David Thompson [1770–1857]:

April 19th. [1811] We proceeded five miles of strong rapids, in places we had to carry the cargo, such as it was, to where the River expanded to a small Lake which was frozen over, and we had to camp, we anxiously wished to clear away the snow to the ground ; but found it five and a half feet deep, and were obliged to put up with a fire on logs and sit on the snow. (3)

The original lake was engulfed by the flooding of the Columbia River valley after the Mica Dam was cvompleted in 1973. Kinbasket Lake is now a 260-kilometer long hydropower reservoir. From 1973 to 1980 the reservoir was called McNaughton Lake, after General Andrew McNaughton. The former name still appears on many maps.

“Kinbasket Lake” is listed in the Indigenous Geographical Names dataset as a word of the Shuswap language.